“I blame my mother and my father for the man I have become.” Terrible Tommy, by Ryan Horn

Beliefs are like herpes: easy to acquire and hard to get rid of.

The cunning aspect of beliefs is the combination of authority and limited perspective. If you encounter a perspective and there is something bigger than you that substantiates the perspective, then it becomes a belief.

The most bigoted person I have met was a San Francisco area Democrat (you can’t make-up stuff like this). He came by his prejudices by being handed a perspective by authoritative persons. Once firmly rooted, casual encounters provided confirmations of his bigoted biases and reinforced his perspective.

His grandfather was a tradesman in the Bay Area before World War II, and thus a solid middle-class white fellow. When the war broke out, people from all over came to the San Francisco area to work for the war machine building ships, runways, moving cargo. This included every lower income class non-white in the catalog. When the war ended, these folks did not leave and started competing for trade work. Hence, Grandpa developed hatred for the people he perceived as diminishing his middle class luxuries.

Gramps handed down his newfound prejudices, along with all the nasty rhetoric to his son and grandson, the latter being that most bigoted person I have met. He then started working for a company in Oakland, traveling on the local train system (BART) and encountering all varieties of people he had been taught to dislike. Any time one individual did something less than proper, this reinforced the San Francisco bigot’s belief system.

Paw-Paw provided him both the perspective and was a source of authority. One survival trait humans possess is not to question authority (too much). Wisdom of the elders is a way of passing along useful knowledge, but it is also a way of passing along bunkum, superstition, and outright falsehoods.

We’ll gloss-over the “perspective” part as we know perspectives can be built out of narrow or broad knowledge, accurate or otherwise. It is the authority part that becomes more important.

My Dad was an authority as well. However, not only wasn’t he a bigot, he was one of McNamara’s Wizz Kids, had a gifted scientific mind, and was a keen critical thinker. Thus, he was a high-quality authority with both honed perspectives but also the honesty to admit when he didn’t know something and thus would guide me in self-discovery.

One day, an older and cooler kid at school (an authority source) ridiculed me. I came home butt-hurt. When I told my father about it, he asked “Why does his opinion matter?” In other words, Dad (the highest authority in my life) questioned the authority of this other kid, which after a moment of contemplation on my part, erased all my woe over the incident.

Looked at chronologically:

- The other kid/authority projected his perspective about me onto me.

- Because he was a source of authority (age and coolness), I accepted it to my grief.

- Dad questioned the other kid’s authority and my acquired belief/perspective vanished.

It doesn’t work this smoothly 99.964% of the time (and given that I made-up that statistic, shows you not to trust any authority without verification). The point is that most beliefs cannot be constituted without some form of authority.

Even A Bad Seed Germinates

“… we search for supporting evidence, and if we find even a single piece of pseudo-evidence, we can stop thinking. We now have permission to believe.”1In the Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion, Jonathan Haidt

Every belief has an origin story, if long forgotten. But this quote foreshadows our discussion on “believable superstitions”.

In short, while we attempt to make sense of our universe, we may construe or hear of an idea. Any evidence, no matter how weak, creates a confirmation. Unlike “confirmation bias”, where one only adopts information that confirms a pre-existing belief, the “seed proof” of any evidence supporting an idea turns it into a belief.

Gather a few stray ideas, randomly encounter a proof point for each, and you have the skeleton of a belief system … or worse yet, a religion.

Additive Function of Beliefs and Religion

Was the first religion a trick? Let’s stipulate that an older tribesman had found ways of tricking others into believing about monsters. Not a big stretch from the general dangers of the jungle. The original boogeyman could have been born of tales about an exceptionally tall, strong and nasty man in a nearby tribe. Like all good stories, it was exaggerated for effect.

But the intertribal boogeyman, vested with exaggerated powers, became a believable superstition as applied to traveling beyond the safety of the local tribal region, the odd cultures of other societies, and the dangers this all created. Over time, the real person – Mister Tall, Strong and Nasty – became a proto-demon. After a generation or two of story embellishment, he developed into a supernatural explanation for other things such as missing children, dead cattle in the field, and bad crops.

Here is the seed of religion. If one can use a believable superstition about a boogeyman to explain misfortune, we have snuck into the realm of transcendence – the going beyond ordinary limits and creating a belief without substantiation.

It is then a small step from augmenting the boogeyman story into the God story. If a tribe is using a Boogeyman to explain the evil in the world, could such mechanics of characterization be used to explain the world in general? It likely started on the polytheistic route, building or borrowing one deity at a time. But the process still finds its seed in a reality (Mister Tall, Strong and Nasty) to explain something unrelated (the believable superstition).

The one fed the next, which fed the next, etc. It is the initial escape from “what we see with our own eyes” to “what we explain from tales” that slips into transcendence, which opens the flood gates for religion.

That is another reason beliefs are hard to change. They are interconnected and additive. Like a Jenga tower, you might be able to remove one or another element of a belief system without the entire structure collapsing … but do you want to risk it?

Forms of Authority

What is authority in this context?

For belief systems, authority comes in two primary modes: experiential and referential.2There are many forms of “authority”, but most deal with “power”, such as the government’s authority to you, your money or your life. “Power” is a source of intimidation, not a source of belief confirmation, at least outside of religion. In that case, an all-powerful god is an intimidating factor and people often choose to believe whatever that god believes.

AI is now an “authority” which is producing some problems.

A new condition called “ChatGPT psychosis” comes about when a person engages and AI, which in turn both agrees with whatever the user believes/says and reinforces that with either viable information or AI hallucinations.

Because of large language model (LLM) breadth of “knowledge”, it is positively god-like in some responses. With agreement on the user’s queries instead of objection pushback, people get reinforcement and even amplification of often delusional beliefs.

As you will learn later, agreeing with a belief is a tool or marketers and propagandists. When a god-like AI agrees with you, it is akin to divine enlightenment.

EXPERIENTIAL AUTHORITY: If as a proto human, you lived at the beach and saw this huge, bright, orange ball rise up from the ocean every day … and not from the mountains behind you … then you have an experience that is authoritative by virtue of consistency. If the sun came up in a different latitude or direction, then you would never have a belief that it would reappear in a particular place.

REFERENTIAL AUTHORITY: This is any means where dicta come from a source, and is believed because the source is trusted (i.e., a tribal elder known for being wise). Take my story about the bully. Had another kid said, “Why does his opinion matter?”, I might have never seriously contemplated the notion. But my father, being reliably smart, was authoritative (our household’s tribal elder) and thus I paid attention and took the advice seriously. Before moving on, we’ll mention “charismatic authority”. When a person has charisma (a compelling attractiveness or charm that inspires devotion), they can be a variant of referential authority.

Without showing my hand too early, referential authority is a big part of religion. God is the ultimate authority, and his earthly handlers (shamen, preachers, imams, priests, etc.) are referential authority because of their alleged superior acquaintance with the sundry words of God.

It is sadly amusing to note that the news media has self-destroyed their own authority. In the 21st century, news organizations abandoned most pretense of partisan neutrality. The public has increasingly grown to disbelieve journalism. But it gets funnier.

News organizations employ “fact checkers” and have on many occasions grabbed their own ideological set of facts to wage political or social war. Caught often enough peddling questionably checked facts, consumers of news media have become suspicious of “fact checkers” in general, unless the checker of facts reinforces the consumer’s belief systems.

This has grown so entrenched within the public that researchers concluded people now “had higher levels of distrust for journalists providing corrections, perceiving them as more likely to be lying and possessing ulterior motives.” In other words, media “fact checkers” had “misled” people often enough that reporters citing “fact checkers” were discounted or dismissed.

Way to go Forth Estate!

MORAL AUTHORITY: One’s morality and ethics are belief systems that are often (and often mistakenly) coupled with righteousness. The terrorist bomber believes they are enforcing their and God’s morality, regardless of how many children die in the blast.

If you have strong moral or ethical convictions, they are its own authority. If those convictions are shared with a group, as they often are, then the effect is compounded.

The problem is that morality is tricky, for it is all based on perspective and everybody’s perspective is different. But to disclaim one’s morality is about as painful as abandoning a community or a God. Thus, propagandists love to communicate the shared morality of large groups as it has built-in, self-referencing moral authority.

MASS AUTHORITY: Recall the experiment about actors and a test subject in a room filling with smoke. The test subject was bending to the beliefs of the masses. If a larger number of people believe in X, then social conditioning and survival instincts can make you believe in X as well. The group becomes the authority due to herd mentality.

This, incidentally, is a big part of both propaganda and to a lesser degree marketing. Throughout the history of propaganda promoters have sought to make “group consensus” appear larger than it is. In modern context, politicians hire hordes of people to echo “talking points” in near unison in order to make undecided voters believe that the community at large wants one or another politician, or their policies. This is highly evident on Twitter/X every second, of every hour, of every day.

Mass authority is so powerful, it can changes a person’s perception of reality, not only on a psychological basis3Asch Conformity Experiments, Autokinetic Effect Studies, , but on a physical one ass well4fMRI studies have shown that the presence of peers can alter brain activity in regions associated with reward processing and risk assessment. Also, researchers have observed changes in neural responses to visual stimuli when participants are exposed to others’ opinions, suggesting that social influence can modulate basic perceptual processes..

INHERITED AUTHORITY: The Scottish side of my family will bristle if you even mention Culloden … despite the war fought there being hundreds of years ago and that they have never visited Scotland.

As children we tend to buy-in to the authority of our parents … at least until we become teenagers, then rebel against the same as our network of influencers expands. We thus inherit from the generations before us much of our belief systems due to the authority of our closest and allegedly smarter elders.

PLAUSABILTY/IMPLAUSABILITY AUTHORITY: Often we face situations where there is no external authority. Instinct (which is a form of authority) instructs us to rapidly determine what is likely. Thus, we are occationally our own authority as we analyze what is or is not plausible, opting for the plausible explanation. A series of merely plausible rationalizations is enough to create a belief system.

GUT AUTHORITY: Recent science has validated the notion of “gut instinct.” The digestive tract “communicates” with the central nervous system in ways whereby the brain changes digestive processes and so forth. Such evolutionary systems that protect us from environmental harm also alert us to social “dangers” and inform beliefs.

NEGATIVE AUTHORITY: Niche, but often providing any contrary opinion – going against the grain – is perceived as authority. If you are dissatisfied with the status quo, and someone makes even half-baked arguments against it, the perception that they have “thought through it” and have some meaningful insight derives from their questioning existing authority. Much of 1960 counterculture was based on this alone.

GENETIC AUTHORITY: There is some scientific evidence supporting the idea that genetics, to a degree, codify predispositions to the environment, which in turn changes how a person who inherited those genes may believe.

Cognitive scientist Shihui Han, among others, notes that brains of people from different cultures respond differently to specific stimuli and social contexts. Your sense of disorientation in a foreign culture might be induced in part by the “authority” of your own genetics. Your lineage might be telling you that what you are experiencing is “not right.”

Societal Norms and Personal Beliefs

People can and do devise their own sets of knowledge, but those are very influenced by the societies and cultures they swim in. The intersection of accumulated knowledge and the force of collective social biases help to define what is perceived as knowledge.

People can and do devise their own sets of knowledge, but those are very influenced by the societies and cultures they swim in. The intersection of accumulated knowledge and the force of collective social biases help to define what is perceived as knowledge.

For example, raw facts long ago pointed to the earth rotating around the sun. But cultural dictates (mainly religion) caused the heliocentric view to be dismissed … and criminalized.

The interplay is important.

The fewer the facts or the stronger the societal biases, the more we generate a belief or believable superstition. The more facts and fact-based knowledge grow, the more it comes into conflict with established cultural biases (e.g., science debasing scripture). Because cultural biases are established and very personal belief systems, any growth of fact-based knowledge will be viewed as a threat to those beliefs, which is a threat to a person’s or institution’s rubric for explaining their world. The response is so strong that a “true believer” will reject hard data showing that their cultural foundation or their belief is called into question.

Windows Slide

Is anyone else tired of the phrase “your own truth”?

Overwrought as it is, it makes a point that “truth” is mainly perspective for the average mortal. With our individual and collective subsets of facts and knowledge, and our varied cultural predispositions, “truth” is highly subjective.

Overwrought as it is, it makes a point that “truth” is mainly perspective for the average mortal. With our individual and collective subsets of facts and knowledge, and our varied cultural predispositions, “truth” is highly subjective.

It is also time sensitive.

History is a collection of perspective snapshots. These snapshots are compiled from incomplete facts, knowledge, and beliefs often grounded in thin air. Compare the snapshots from the Jews in ancient Egypt, to Roman Empire citizens, to feudal lords, to enlightenment thinkers, to American evangelicals of the 19th century, to people habituating a San Francisco sex club. The history of the moment and place defines the current belief systems.

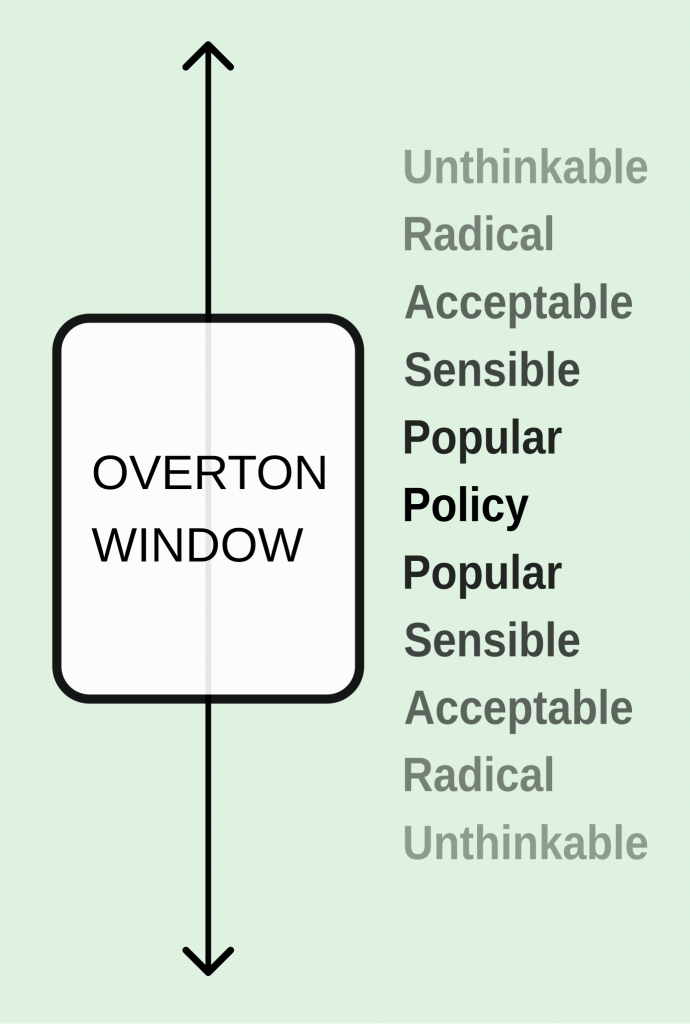

This was the maternity ward for the Overton Window, which states that there exists a range of policies politically acceptable to the mainstream population at a given time. But that scope of acceptability changes and the window shifts. Along with it, so do the societal and cultural pressures that butt heads with facts and knowledge.

Indeed, they change knowledge. Before 1973, the American Psychiatric Association defined homosexuality as a mental disorder in their Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. It can be argued that the cultural earthquake called the 1960s changed public perception, which changed the science, which then opened a new sash on the Overton Window (albeit slowly … the American Democrat Party did not officially embrace same sex marriage until 2012).

This sliding window effect also creates intergenerational resistance. The “olds” may cling to the belief systems on which they were raised which then makes their notions (even when right) appear outdated. But as Robert Anton Wilson noted, “It only takes 20 years for a liberal to become a conservative without changing a single idea.”

Comments

How We Acquire Beliefs — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>